Artists should view the advance of AI technology as an opportunity rather than a threat, according to the team behind Tate Modern’s upcoming tech-focused show, Electric Dreams. Catherine Wood, the London museum’s director of exhibitions and programs, explained that the exhibition highlights the long-standing relationship between artists and technology, emphasizing their intertwined futures.

Opening on November 28, the Electric Dreams exhibition will showcase more than 150 works by 70 artists from around the world. “As a museum, we wanted to say this is not a new conversation,” Wood said. “It’s not a new existential threat for creativity. Humans and artists have been grappling with these questions for a long time so we wanted to give the long view on the social, existential, and artistic questions around uses of technology to make art.”

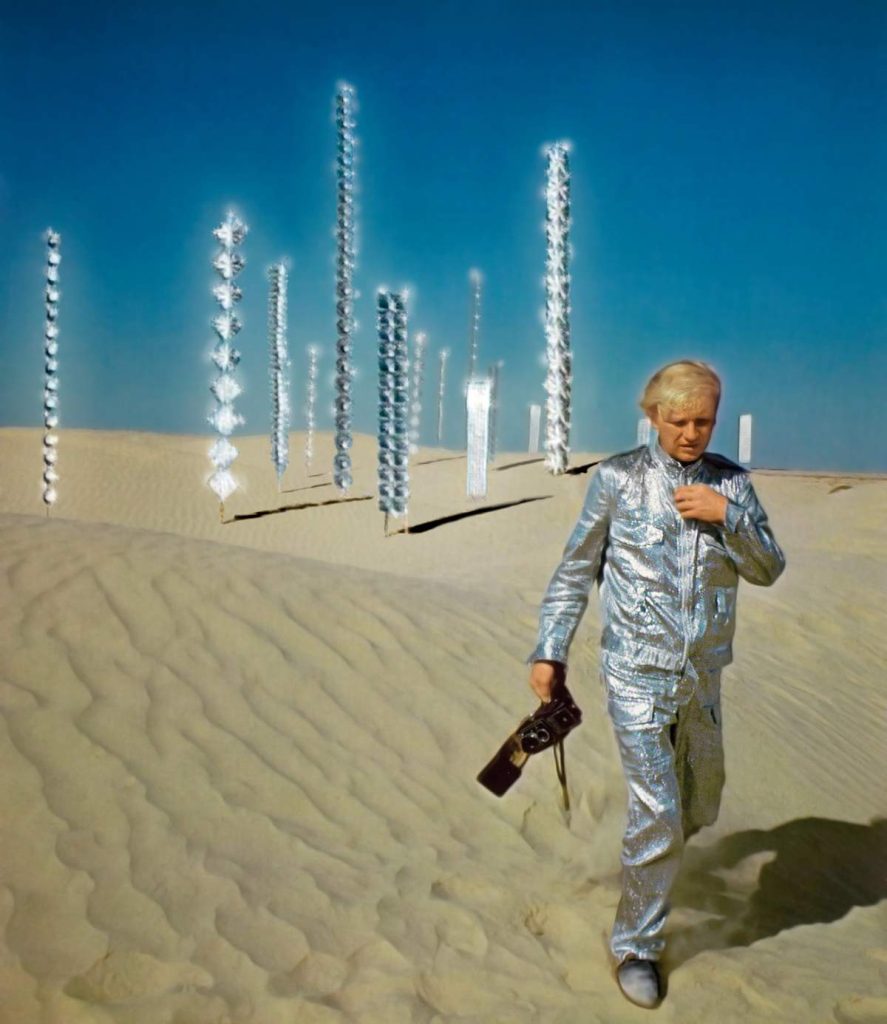

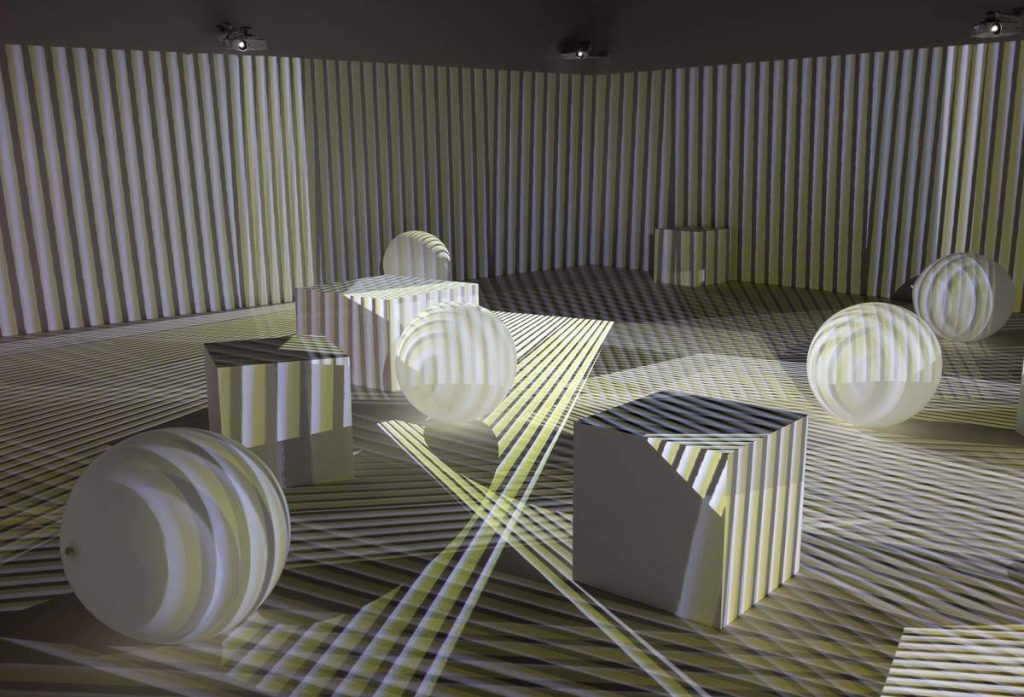

The exhibition includes decades-old technology, with pieces like Otto Piene’s Light Room (Jena), where light creates “sculptures” in a darkened room, being displayed in Britain for the first time. Electric Dreams spans from the 1950s through the “pre-internet” age, though Wood notes that artists then were already preoccupied with modern concerns about technology’s use and control.

“Art has never just been about crafting images or making imaginative pictures,” Wood stated. “All the artists in the show are grappling with their being, and the technology is a prosthesis or a tool. How those two things come together is what the show focuses on.”

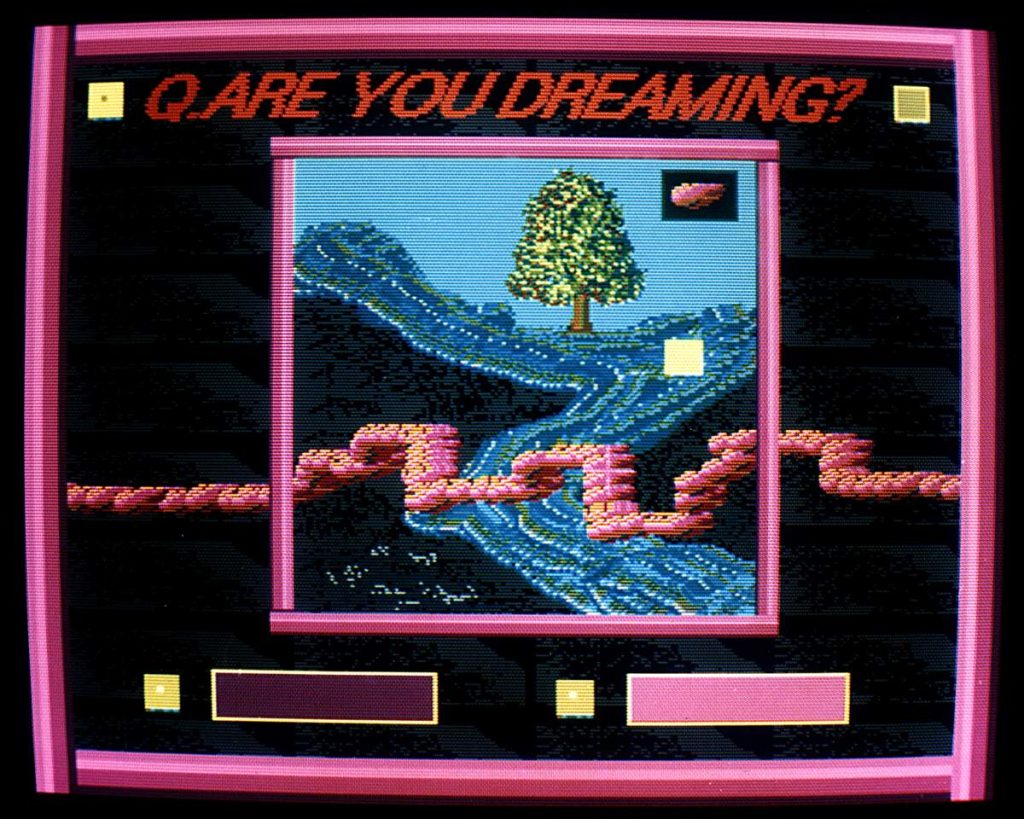

The exhibition features works that seem surprisingly contemporary, such as Harold Cohen’s paintings created by “drawing machines” using AARON technology, widely considered the first AI technology for making art. There are also immersive pieces by artists like Carlos Cruz-Diez and the German duo Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss, which were early forerunners to modern Lightroom shows.

Despite initial skepticism towards pioneers like Harold Cohen, Wood believes their work remains relevant. “At the time with Harold Cohen, people did think it was gimmicky and it was marginalised. People were suspicious but from this vantage point he was a real pioneer and a visionary,” she said of the artist who represented Britain at the 1966 Venice Biennale.

Wood also highlighted Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress from 1956, illustrating the innovative spirit of Japanese artists willing to take risks and pioneer new styles. “It was partly the technology in Japan but it was also the attitude,” Wood explained. “The Gutai group she was part of was making the process of making art a theatrical spectacle and making it visible in ways that feel completely philosophically natural in our age of sharing everything on social media.”

One challenge in assembling Electric Dreams was getting the old technology to function. Tate’s “time-based media team” worked to ensure the hardware, including Cohen’s drawing machines, were operational. “They need quite a lot of coaxing,” Wood noted. “It’s often a question of do you preserve the object at the expense of it being able to act? We need these things to be actually working and acting. We want them to be interactive.”

The conversation about artificial intelligence and art continues to be contentious, with several class-action lawsuits in the US from artists claiming their work has been used without permission by AI companies. This year, Ai Weiwei told the Guardian that art easily replicated by AI is “meaningless.” He added, “I’m sure if Picasso or Matisse were still alive they will quit their job. It would be just impossible for them to still think [the same way].”